tw: intimate partner abuse, sexual assault, racism

It was maybe, five or six years ago? More? I remember it was a sunny day. My husband, brother- and sister-in-law and I were all at some art museum in the South Bay. I don’t really remember the art. I remember the sun, because Chicago is cloudy most days from November to April, so it was likely during a holiday we were visiting, and sun was a gift.

And I remember the gift shop employee.

A white woman, in her late fifties, with dyed hair cut into a stylish but unfussy pixie. Lots of glittery jewelry. Rouge, and mascara clumping in the corners of her eyes.

I remember something tugging on my ribcage-length locs.

I turned, and she was staring at me like I was the $400 geode bookends in the display case or something. I rolled my eyes. “Yes, this is all my real hair,” I replied to her unanswered question. We talked over each other—or rather, she interrupted me—to compliment me on my hair. I weary of white people and their morbid-cum-fascinated curiosity with the black body; but I am a woman, and I was raised in the Midwest, and I was taught not to make waves with white people, that being agreeable keeps you alive, AND, I’m with my in-laws, a well-meaning but unsteady relationship even on the best of days, so I have to behave. I asked her if she wanted to touch it. She tossed a comment over her shoulder and walked away, and only then did I realized that she had. The tug I’d felt had been her long, lacquered nails in my hair.

Do people touch your hair without asking? Do perfect strangers feel no compunction about laying their hands on your body, to test the veracity of what they perceive, or because they’re enthralled, or appreciative?

I still fantasize about unloading my rage on her, about getting loud and telling her how utterly inappropriate it is for her to yank on the hair growing out of my scalp, even if she thinks it’s beautiful. I am a person. I have a body. I exist in my body because God wanted to incarnate in my particular way, and for whatever reason, I consented to be a part of that, and my parents made me. I do not exist to entertain or be used by anyone for anything. When people like this woman lay hands on me without my consent, they demonstrate they don’t actually see that I exist as a person, with thoughts, desires, needs, agency. They treat me like a doll, like a toy she can pick up, play with, and set down. I am inanimate. If I am so inanimate that I can be pulled and tugged like a pickaninny doll, then what else can people do to my body? Can they assault me? Can they rape me? Can they shoot me while I’m surrendering? Can they tie me to the bumper of their pickup and drag me through the streets?

Let me be clear: I would not have been happy to let her touch my hair. I know a lot of white women, and I love most of them, and I struggle with being the (only?) black woman they know with interesting (is it? for just being itself?) hair and some of them want to coo over it and remark about how long it’s gotten and how I care for it and… you know this narrative. So I can’t even say that I would have felt differently if she’d asked. Probably not. But if she’d asked, it would have shown that she saw me as a person, and not as an object. She would have given me the opportunity to consent to a physical, hands-on relationship, even one that lasted for five seconds. She would have given me the right to consent. She would have indicated that she understands that I have power over my own body and how it interacts with others, and she does not.

She would have recognized me as alive. As apart from her and the world that bends to her will.

She would have seen me.

*

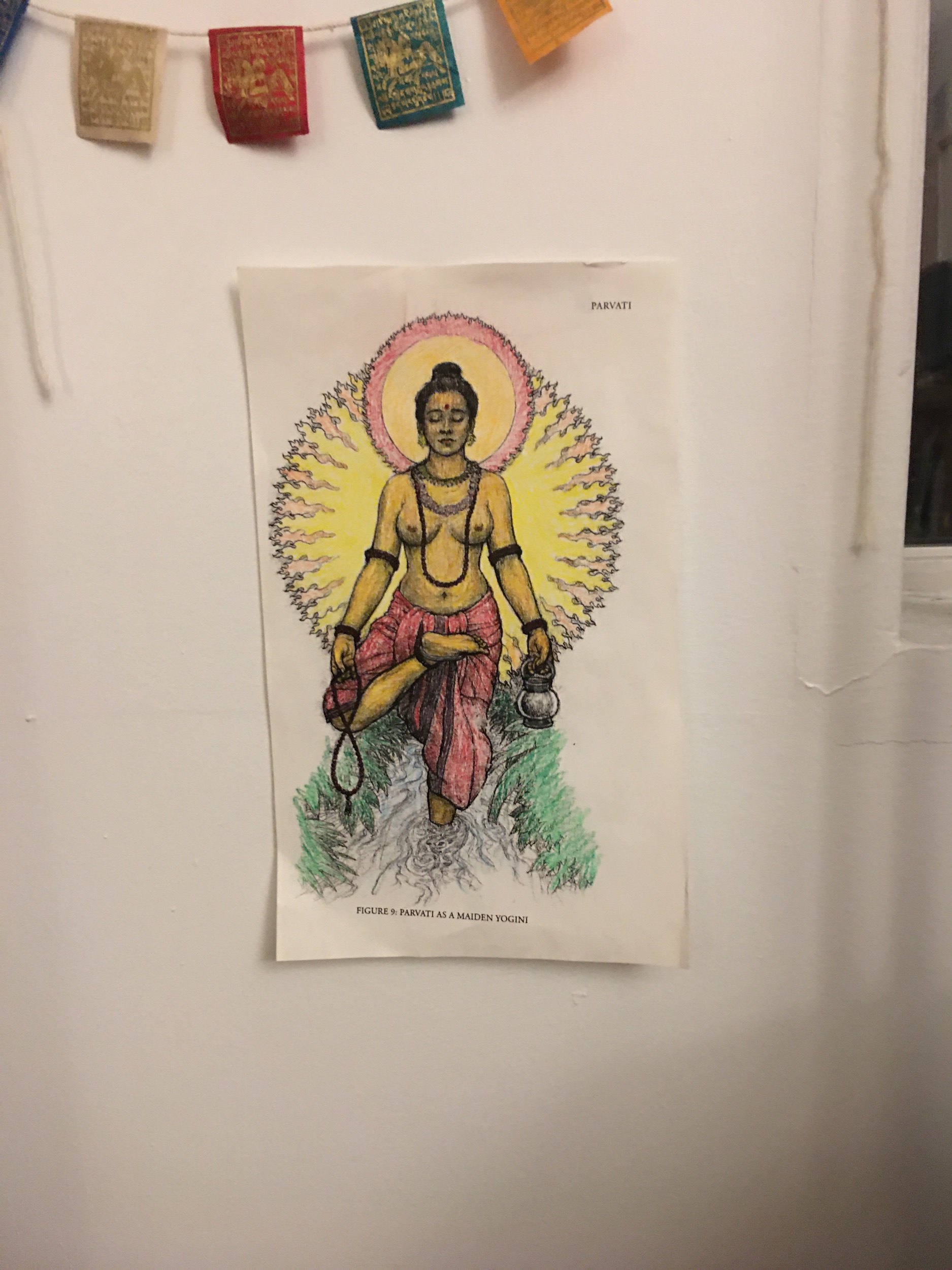

A friend and fellow healer learned that I wrote a paper this semester about the Virgin Mary and the Hindu Goddess Sita, and the role that consent plays in their narratives. She asked me if she could read it, and on the off chance that anyone else is curious about it, I told her I would post a portion of it here, and not send her the whole 12 pages. I won’t past the whole 12 pages either. It’s… it was really interesting to me that this young, unwed woman who’d allegedly been raised to be a holy person in the temple her entire life was given the opportunity to consent to her role in the entree of Christ to the world. God knows about consent: if God asks Mary’s consent, what’s our excuse for not asking one another? Additionally, Sita is held up as this long-suffering wife who lets her husband, Rama, throw shade and cast judgment on her fidelity, her strength and her morality repeatedly. But when I shift my lens a little, I can see that Sita consents to this behavior, especially when I consider the way she goes out.

It was a fun paper to write. It would have been even more fun if I’d felt free to write the way I like to, and I wish I’d had the energy to really make it as strong as I can imagine it could have been. I’m writing a lot at school, which feels incredible, but there’s a fair amount of expectation for that academic voice, which feels stilted and artificial. It feels absent audience and I feel constricted by it. I got an A minus. It’s a decent grade, I guess. It’s a bit sticky to know that it wasn’t my best work and to have that confirmed, yep, strong, but not quite the thing. I haven’t done much rewriting for this audience: I have tried to sand off a bit of the academic edges, but you might not recognize my voice.

*

One wonders if Mary knew fully what she was consenting to when she told Gabriel Yes: had she known how hard Jesus would be tested, gossiped about, persecuted, had she known the gruesome nature of his suffering and death, would she have chosen to be his mother. Not only must she suffer the trauma of watching her child be put to death, but before he even arrives, there are narratives of hers that illustrate the complex and unpleasant experience she has for being chosen as Theotokos. In the infancy gospel of James, Mary repeatedly forgets that she is carrying Jesus, and is subject to mistrust, judgment, and anger from Joseph, as well as judgment and a test of her fidelity from the priests at the temple. [1] In Surah 19 of the Qur’an, Mary delivers Jesus alone, in great pain, under a date palm and wishing herself dead.[2] Luke conveys none of this suffering in his gospel, but if we create a narrative based on the composite of these three accounts, we can see that Mary’s consent was a loaded act, charged not only with potentially Jesus’ suffering, but her own. Aaron Riches makes a case for the risk that Mary undertook in her consent to herself, as well as what makes Mary’s consent so powerful in Jesus’ life: “Mary’s fiat does not merely consent to all that will befall the Son; but more, her fiat fully participates in all that will befall the Son: the dregs of his deprivation, the bowl of his staggering and the suffering wound of his cruciform way.”[3] While not convinced that Mary knows Jesus’ fate in the moment of her consent, I can concede that the consent Mary offers puts her in considerable risk in her own context: Mary was a young woman, unwed, an ethnic minority in the Roman Empire, and the risk of being found out to be pregnant could have cost her her life.[4] In consenting to the will of God, Mary was consenting to having her own life be changed by God. She was creating space for the sacrifice of Jesus, and she was also making herself a kind of willing sacrifice: consenting to suffering, but by the birth of Jesus, also consenting to a role in the world’s redemption.

In this way, Mary is a promise kept that was broken in previous generations. She “is the embodiment of the faithful remnant of the people of Israel.”[5] Luke’s narrative affirms this: it is the only version that both empowers Mary with consent and with the Magnificat, a song of praise for how the world will be set right by the result of her consent, namely, the birth and life of Christ. When visiting Elizabeth, who is also pregnant by the hand of God, Mary says, “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant… [T]he Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is his name.”[6] In choosing Mary as his delivery method for Christ, God has “scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts,”[7] has “brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty.”[8] What a legacy of justice and righteousness Mary has become a part of through her consent. This passage goes a long way toward affirming the idea that Mary’s consent, though fully her own, is affirmation and restoration of a line of prophesy that was made with the nation of Israel: “the Annunciation is the paradigmatic icon of the creaturely act of receptivity to the divine call, which means that Mary’s fiat fulfills the Abrahamic response [of Genesis 22].”[9] Not only is Mary’s consent a clear moment, but its consequence reach back into the past, as well as into the future of Jesus’ life, and the lives of his followers. Her consent is powerful.

Sītā’s consent is more complicated. Like Mary, consent in Sītā’s narrative results in her surrender, in Sītā’s case, to the will of her husband, Rāma. However, unlike Mary, Sītā is not uttering a clear, emphatic Yes in her own story; instead she is often protesting, but at the same time is surrendering to the task asked of her. One of the most pivotal scenes wherein Sītā is put to the test to see if she will consent is in the Trial by Fire, the Yuddha Kandha of the Rāmāyana. After having been kidnapped by the demon king Rāvana, she is rescued and returned to Rāma, his brother, Lakṣmana, and his royal court. However, Rāma is not happy to receive her. He believes that Sītā has been unfaithful to him while she was hostage, and he spurns her devotion. Rāma tells her, “‘Since, however, your virtue is now in doubt, your presence has become [..] profoundly disagreeable to me… I do not love you anymore. Go hence wherever you like.’”[10] He banishes her from his sight and his kingdom, despite her fealty and fidelity.

Sītā has perhaps only one way to act from here: to grant Rāma’s wishes and leave. Sītā does not do this; again, like Mary, Sītā defends her fidelity and her devotion. “‘If I came into contact with another’s body against my will, lord, I had no choice in this matter… My heart, which I do control, was always devoted to you.”[11] Bereft as she is, Sītā does not see departing from Rāma as a real option: for to do so would be to confirm the suspicions about her that seem to have swayed Rāma to this point. Her commitment to their relationship is so complete that if Rāma does not want her, then she can see no other way to live. She asks Lakṣmana to build a pyre and steps into it. Is this Sītā’s choice? It is arguable that Sītā cannot consent because she is coerced into an act like this. But when we look at Sītā’s story in full, we will see that even this act is a choice that Sītā makes. Even in this, she consents to Rama. Her choice to have a funeral pyre build before Rāma and his court is a kind of consent in her behavior: she is continuing to consent to her husband as the lord of her life. The pyre serves as a witness to her honesty and as a testament to the tapas of her fidelity and virtue. Before stepping into the fire, Sītā utters, “‘Since my heart has never once strayed from Rāghava, so may Agni, the purifier, witness of all the world, protect me in every way.’”[12] It is clear that Sītā believes the fire is will bear witness, will exonerate her fidelity to Rāma. She is not committing suicide (an act often maligned, specifically in this context, where women taking their own lives by entering their deceased husbands’ funeral pyres is a practice named for Sati); she is purifying her witness to her own truthfulness. In a sense, by entering the pyre she is “doing what she wills”, which is what Rāma has asked, but also, she is continuing to maintain her devotion only to her lord, Rāma. While this is not the clear, emphatic Yes that Mary gives, it is an important act: like Mary, Sītā surrenders in this choice. She defends herself and her virtue, and then she offers herself to the fire to prove herself…

Mary and Sītā both undergo a span of challenge in their narratives: … Mary… is plagued by forgetfulness, she travels a long distance while far into her pregnancy, and significantly, she repeatedly has to defend her virginity to her husband, as well as to priests in her community. Similarly, Sītā is repeatedly tested and challenged by her own husband, Rāma. After being rescued from her kidnapper, she is scorned and spurned, and whether by command or because she feels she has no other recourse, she consents to immolate to prove her fidelity and purity. Rāma accepts her back, but after a time he allows his pride and insecurity to make him believe that Sītā is not devoted, and again, he casts her out: he charges his brother with taking her, pregnant with twins, into the wilderness and abandoning her near an ashram. She is left to roam the wilderness and to birth and raise her sons alone, and a sadhu discovers her and takes her into the ashram. This sustained testing shows both women’s strength. Despite humble circumstances, and indignities and humiliations leveled at them, both women choose to consent in such complex circumstances.

Sītā’s narrative takes a turn in a different direction, and her consent leads her away from Rāma. Rāma once more orders Sītā back to his court, to swear that her sins have been cleansed and that she is blameless. Rāma is attended by Sītā and her twin sons, as well as by many sages who bear witness to Sītā’s purity and fidelity. When it comes time for Sītā to speak, while honest and without reproach, her tune has changed. Sītā is no longer willing to remain steadfast by Rāma’s side while he judges and mistreats her.

When Sītā, who was clad in ochre garments, saw all those who were assembled, she cupped her hands in reverence, cast down her eyes, and lowered her face. Then she spoke these words: “As I have never even thought of any man other than Rāghava, so may Mādhavī, the goddess of the earth, open wide for me.” And as Vaidehī was thus taking this oath, a miraculous thing occurred. From the surface of the earth there arose an unsurpassed, heavenly throne… Then Dharaṇī, the goddess of the earth, who was on that throne, took Maithilī in her arms and, greeting her with words of welcome, seated her upon it.[1]

Like with Agni in the Trial by Fire, Sītā asks the Divine Earth to respond to her as a witness to her behavior and purity of heart. For the first time in the story, Sītā leaves Rāma. She says, No: she no longer consents to being mistreated or mistrusted. She knows her strength and fidelity, and she will no longer consent to Rāma making her prove herself over and over or doubting her and so casting judgment on her based on the gossip of his people or his own insecurities. Much like the dutiful wife she is, when she has had enough of being mistreated, she goes home to her Mother, the Earth. As one of Madhu Kishwar’s interlocutors puts it in an interview, “… her appealing to Mother Earth to take her back into her bosom should not be interpreted as suicide. It is a statement of protest, that things had gone beyond her endurance limit. It amounted to saying: ‘No more of this shit.’”[2]

Though Sītā’s consent—to essentially continue to receive the mistrust and doubt of her husband, as well as to engage in his tests of her fidelity and her mistreatment repeatedly—looks different than Mary’s willing consent to be the mother of God and to undertake all the suffering contained within—of having her virginity tested and doubted, as well as outliving her son—both women practice consent as surrender. They choose to allow what befalls them to stand, unless or until they no longer choose to, in Sītā’s case. Consent is in both narratives an act of surrender. Consent is not a passive way of being; both women are moving toward a thing. If we consider the Wheel of Consent as a kind of model for their behavior, we might place Mary in the “Accept” quadrant in the lower right corner. Mary gives herself over and accepts the Holy Spirit to her, and in this way, she consents to be Theotokos. Sītā’s role places her in the “Allow” quadrant, the bottom left: Sītā allows Rāma to misjudge and mistrust her, to the point where she consents to self-immolation to prove herself worthy of him; she allows him to banish her, pregnant with his own children, from his kingdom, into the wilderness. She routinely protests her innocence and faithfulness, but she never considers leaving Rāma, faithful to him in her heart and in her actions, even when they are apart. Ever the devoted and dutiful wife, Sītā allows Rāma to think the worst of her.

Both Mary and Sītā have power in these circumstances. Even Sītā, who seems powerless in her case, is choosing to consent. It would be easy to portray Sītā as victim. In an ethnography of the role of Sītā in popular culture by Kishwar, one woman interviewed says that while Sītā is an ideal wife according to Indian societal norms, that, “[Sītā] should have rebelled more. She should have refused even the first agniparīksha.”[4] But our frustration with Sītā is part of what makes consent so compelling: her consent, even to mistreatment, is what empowers her in this narrative. Though Rama does not know or acknowledge it, Sītā has as much power as he, power over her own willing presence in his life. She chooses to surrender herself to his (mis)treatment of her, until she decides she has had enough. Sītā’s final refusal and departure is vital to the Rāmāyana: this is the moment that shows all her longsuffering was not just by her husband’s will, but by her own. Power was in her hands the whole time.

David Kinsey writes, “Sītā’s self-effacing nature, her steadfast loyalty to her husband, and her chastity make her both the ideal Hindu wife and the ideal pativrata [devoted wife]. In a sense Sītā has no independent existence, no independent identity.”[5] This would certainly be an easy point of view for us to take, but it erases the presence and importance of Sītā’s consent. If Sītā is, as Kinsley labels her a few pages later, an intercessory for Rāma, then she must be able to see both herself and Rāma as individuals. Even as her actions and choices are to prioritize Rāma and the unitive space of their relationship, the Srī/Viṣṇu connection of which Rāma seems repeatedly to be reminded, Sītā is able to recognize herself, at least in some part, in order to try and intercede for others. In the Srī Guna Ratna Koṣa, we read a verse wherein Srī acts as an intercessory: “Mother, Your beloved [Viṣṇu] is like a father/ yet sometimes His mind is disturbed/ when He also becomes a font of well-being for totally flawed people;/ but by Your skillful words—“What’s this? Who’s faultless here?”/--You made him forget,/ You made us your own children, You are our mother.”[6] Here, Srī (Sītā) reminds Viṣṇu (Rāma) that he is not without fault, he has also made mistakes, and because of this, should be more gentle and gracious with his children. This verse reminds us of the way in which Sītā functions for her devotees, “not approached directly for divine blessing but as one who has access to Rāma, who alone dispenses divine grace.”[7] In this way, as an intercessory, Sītā is quite like Mary, who also intercedes for her people. “[Mary] has become the mother of all Christians and all human beings… Assumed into heaven, she intercedes constantly for her children…”[8] Mary and Sītā both function as intercessors: their acts of surrender, their acts of consent, are what make their ability to seek favor with the Gods on our behalf possible.

What do we discover by reflecting on surrender as consent? Sītā and Mary have both functioned as models, particularly for women, of purity, blind devotion, and receptivity; often, these ways of being have been used to control and dominate women. Says one of the contributors to Kishwar’s work, “Even if the whole of society is bad, a woman can live a good life as long as she has a good husband. But if her husband turns out to be bad, there is no place left for a woman.”[9] But if we consider that consent is a choice—a moving toward, an action—and not a passive reception, we discover strength and agency examples to draw on. There is great power in consent, not just in what it makes possible for others, but for the sense of self-direction, and of relationship that it creates for the individual. Mary shows that consent allows us to be active participants in relationship with God, in the transformation of our own lives, and in the lives of others. Sītā shows that we are strong enough to consent to suffering if we believe that the suffering is somehow in service of our will or in service of something good to which we’re willing to subject our will; but we are not the victims of the whims of a God who seeks to cause us suffering. We control our consent and our refusal, and when we want to stop, we stop.

*

The footnotes don’t translate well, but I’ll add a bibliography for you to check out if you’re really curious.

*

It’s interesting to write a post like this during Advent: a season I’ve only observed—and that only by thinking about it and connecting to some resources that have offered great content for reflection—for the first time in my life this year. A season of repentance and reflection, of darkness and anticipation, of knowing that the birth of Jesus is coming and trying to get right in order to be ready to receive him, even though we don’t have to “be ready,” we just have to receive. I heard a sermon recently that compared POTUS to King Herod, and talked about how this weak, squeaky, smooshy-faced, brown-skinned baby came into the world as an absolutely political story. A religious (and ethnic? debatable?) minority in occupied territory who was only able to exist without being killed because another country allowed him and his parents to traverse their border, in attempt to escape an insecure, neurotic, racist, despotic national leader who actively plots to destroy his opponents so he can stay in power. In the midst of all this, a teenage woman told a strange, supernatural visitor that God could have his way in her life. In a not-too-distant religious tradition, a woman in relationship with a man who was nervous about his status, who surrounded himself with people who would validate his uber-masculinity and who routinely treated his partner like inconstant, lying garbage, (projection, arguably) his wife, a divine being of the Earth herself, kept saying Yes, kept giving her man time and space to try and work out his issues, because she knew she could handle it. These aren’t women who are small and polite, meek and accommodating. They’re women who know the value of their word.

This season, I feel tired. And angry. And weary of being nice. I am impatient and frustrated and sick of having to argue for my right to exist. I want to shout at people, to curse people, I want to fight.

I need help.

So what do I need to consent to? So often, Yes looks like moving forward for me. Is it an act of surrender right now? What do I do?

All I can think to do right now is to keep looking toward brave women, articulate, thoughtful, compassionate, who aren’t afraid to speak up, who aren’t afraid to set boundaries, and who know the value of consent. In the classroom, on the mat, in the street and online. I’m watching. Listening for the yes and the no.

p.s. bibliography

Bible Gateway. “Bible Gateway Passage: Luke 1 - New Revised Standard Version.” Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Luke+1&version=NRSV.

Boff, Leonardo. The Maternal Face of God: The Feminine and Its Religious Expressions. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1987.

Clooney, Francis X. Divine Mother, Blessed Mother: Hindu Goddesses and the Virgin Mary. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Goldman, Robert P., Sally Sutherland Goldman, and Barend A. van Nooten, eds. The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume VI: Yuddhakāṇḍa. Critical ed. edition. Princeton University Press, 2009.

Kinsley, David R. Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Hermeneutics: Studies in the History of Religions. Berkeley, [California]; Los Angeles, [California]; London, [England]: University of California Press, 1986.

Kishwar, Madhu. “Yes to Sita, No to Ram: The Continuing Hold of Sita on Popular Imagination in India.” In Questioning Ramayanas: A South Asian Tradition, n.d.

“Mariam,” Surah 19.” In The Study Quran. HarperOne, 2015.

Martin, Betty. English: Graphic of the Wheel of Consent with Shadows. April 15, 2015. Betty Martin. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wheel_of_Consent.jpg?fbclid=IwAR1XoKtf7HrfAg7ZulYLMJAWEkX2RXb9oK2nsWRs9cOpV-mqrGOLEIQqd9c.

Miller, Robert J. The Complete Gospels: The Scholars Version. 4th ed. Salem, Or.: Polebridge Press, 2010.

Riches, Aaron. “Deconstructing the Linearity of Grace: The Risk and Reflexive Paradox of Mary’s Immaculate Fiat.” International Journal of Systematic Theology 10, no. 2 (2008): 179–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2400.2008.00352.x.

“The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India: Uttarakhanda.” Accessed December 12, 2019. https://muse-jhu-edu.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/chapter/1899977.

Tulasīdāsa. The Ramayana of Tulsidas. [1st ed. Calcutta: Birla Academy of Art and Culture, 1966.

“What Consent Looks Like | RAINN.” Accessed December 10, 2019. https://www.rainn.org/articles/what-is-consent.

Yarnold, Edward. “The Grace of Christ in Mary,” n.d., 10.