One of my classes this semester is Contemplative Prayer in Christianity. It’s great. I have a great semester of classes, but I can’t stop talking about this one so I guess it’s my favorite. I am eager to consider how it will transform in an online context. It’s tremendous. So if you’re visiting this space from Contemplative Prayer, welcome. In preparation for our conversation on Thursday, try out the following practice.

Supplies:

your copy of Chapters on Prayer by Evagrius (or another contemplative or sacred text, if you’re doing this practice but not in class with me, or a mantra or intention you’re working with).

your journal, a notebook, or a piece of paper (this is not a practice you can perform on a computer. Do it longhand, trust me.)

At least one, and as many pens as you like (feel free to use different colors or widths. You’ll see why as we carry on.)

a timer (optional). This practice only took me about 15 minutes, and it can take you shorter or longer than that. If you’re pressed for time, I’d encourage you to set a timer for 15 minutes, and get as far as you can in that time. It’s not a race though, so the timing isn’t really important. What’s important is the experience you have with the text—it’s rhythm, its consistency, its voice; what happens to you and in you as you work with it.

Take the time to read through the steps before you complete the activity.

Steps:

1. From your text, choose a sentence or line that spoke to you this time around. Think one sentence or one line. A complete thought. A paragraph is likely too long. I chose two sentences.

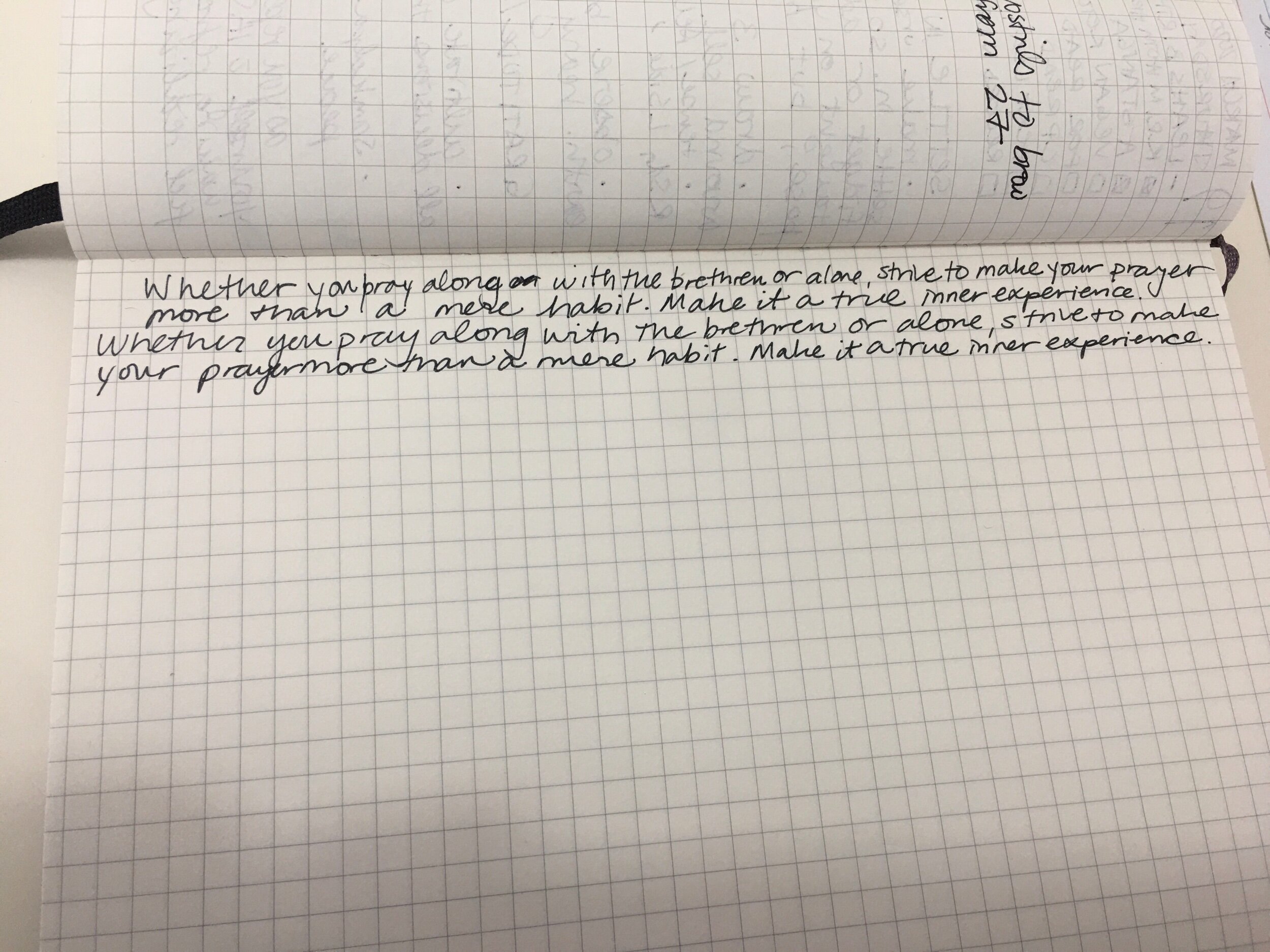

“Whether you pray along with the brethren or alone, strive to make your prayer more than a mere habit. Make it a true inner experience. ”

2. Write the line down, word for word, on your piece of paper.

3. Write it down again, right beside the first line.

4. Write it down, over and over, word for word. Notice what happens inside you as you write the line over and over. This isn’t a test. Are you having trouble remembering it? Have a look at it as you write it down, until you can remember it. Is it echoing? Can you hear the text repeating itself in your head? Do you repeat the text in your own voice as you write it? Are you forgetting words, or adding words? Notice what’s happening. Take your time. You might even want to say it out loud as you write it.

5. Don’t be afraid to get a little creative with your writing. Want to change shape or direction? Do it.

6. Or get a lot creative with it. Use one or several colored pens. Allow the sentence to blossom and expand, and see where this practice takes you.

7. See if you can finish a shape or fill a page. This should be fun, and while it might be generative, it shouldn’t be difficult or stressful. Notice what’s happening.

Take note of your experience trying this practice, so we can talk about it in class. Something to consider: you don’t have to be bound by the shape of the paper. You can use a different shape (like the circle that I used) or any other shape the passage feels like it lends itself to. This might also be an opportunity to explore sacred geometry and how it might affect the phrase you’ve chosen: does a circle, a triangle, a yantra, or a cross feel like a meaningful shape? Feel free to try writing the sentence or phrase in that shape, and see what happens. The creativity should be an option, not an obstacle. This practice is called Likita Japa: a devotional reading and writing practice. (I learned it from Chanti Tacoronte-Perez and Tracee Stanley.) Have your paper available to show and talk about when we meet next. Can’t wait to talk more about it on Thursday!